Written by: Mahmoud Demerdash

Date: 2025-12-25

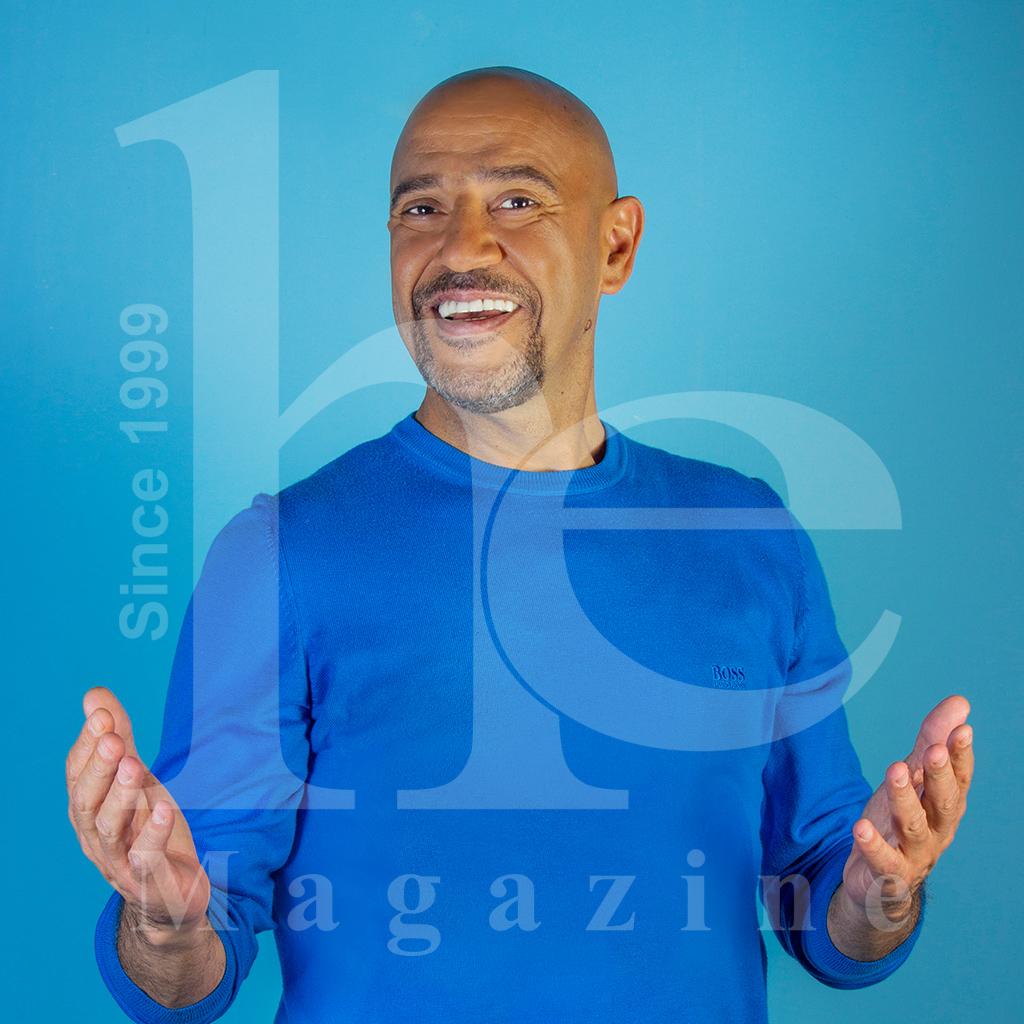

An Exclusive Interview with The secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities Dr. Mohamed Ismail Khaled

Stepping into the old Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square feels less like entering a building and more like crossing a threshold in time. Its high ceilings, marble floors, and quiet, dignified aura embody a spirit no modern structure can replicate. This is the museum generations of Egyptians grew up imagining whenever they heard the word “antiquities”, a place that has safeguarded the nation’s treasures for more than a century.

On a recent visit, He Magazine had the privilege of exploring its halls with Dr Mohamed Ismail, the Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, whose lifetime of work has been dedicated to preserving and interpreting Egypt’s ancient soul. As he guided us through the galleries, he stopped before a masterpiece many visitors underappreciate: the golden funerary mask of Pharaoh Psusennes I, an object he believes deserves to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the world-famous mask of Tutankhamun.

What followed was a sweeping conversation about legacy, rediscovery, and the future of Egypt’s oldest museum, one that continues to evolve even as it remains an icon of the past.

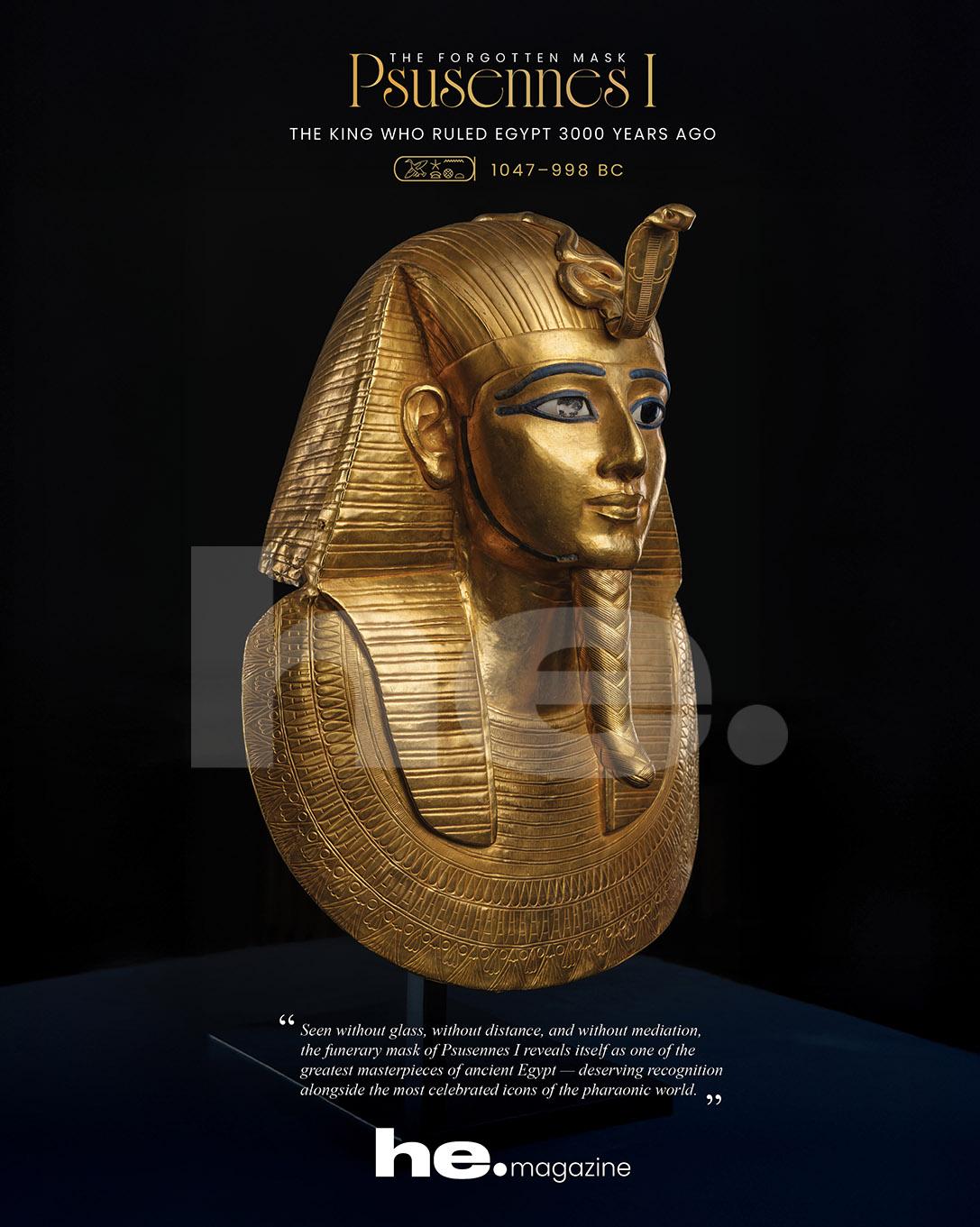

Psusennes I, the Second Mask

Dr Ismail led us toward one of the museum’s most overlooked marvels: the exhibit of Psusennes I. Standing before the gleaming silver sarcophagus, he explained that “the tomb was found was pure silver and in beautiful condition, one of the rarest finds”. It was discovered in 1940, at the height of the Second World War, a period that unintentionally obscured its global impact. Despite the extraordinary craftsmanship and brilliance of Psusennes’ gold funerary mask, he noted that its fame never matched that of Tutankhamun. “The reason why Psuennes’ gold mask discovery didn’t reach the levels of King Tut’s was that it occurred during the Second World War, so a lot of the headlines were diminished as a result”. Yet as he gestured toward the mask, its artistry refined and its presence commanding, he made it clear that Psusennes deserves recognition equal to that of Egypt’s most celebrated boy king.

Psusennes I’s gold funerary mask invites inevitable comparison with the iconic mask of King Tutankhamun, yet the two reflect very different historical contexts. Both masks are crafted from gold and display the timeless symbols of Egyptian kingship, the Nemes headdress, false beard, and idealized facial features meant to convey divine authority. However, Psusennes I’s mask is notably more austere and restrained in its decoration, lacking the extensive inlays of lapis lazuli and colored glass that characterize Tutankhamun’s more visually opulent mask. This stylistic simplicity does not imply lesser status; rather, it reflects the political and economic realities of the Third Intermediate Period. While Tut’s mask embodies the exuberance of New Kingdom wealth, Psusennes I’s mask emphasizes dignity, tradition, and continuity, reminding us that royal power endured in different forms even as Egypt’s resources and artistic priorities evolved. Psusennes I’s silver sarcophagus stands as one of the most striking and often misunderstood symbols of royal wealth in ancient Egypt. As Dr Mohamed Ismail explained, during Psusennes I’s era, silver was considered more valuable than gold, largely because it was not naturally abundant in Egypt and had to be imported through long-distance trade networks. Gold, by contrast, was relatively accessible through mines and therefore more familiar to Egyptian craftsmen. The decision to entomb Psusennes I in a coffin made almost entirely of solid silver was not an artistic coincidence, but a deliberate statement of his supreme royal status. In this context, silver functioned as the ultimate prestige material, elevating the burial beyond even the famed golden tomb of Tutankhamun.

During our visit, He Magazine was granted rare, special access to the exhibit, offering an intimate look at these extraordinary artefacts beyond the standard public experience. In an exceptional gesture, the museum staff carefully removed key items such as Psusennes I Funerary Mask and Psusennes I Silver Coffin from their protective boxes, allowing us to photograph them and fully appreciate their craftsmanship, scale, and material presence, details often lost behind glass. This level of access not only enriched our coverage but deepened our understanding of the objects’ historical and cultural weight. We extend our sincere thanks to Dr Ali Abdel Halim, General Secretary of the Old Museum, whose support and cooperation made this exclusive access possible, and whose commitment to sharing Egypt’s heritage continues to elevate how these treasures are documented and presented to the world.

The Appeal of the “Old” Museum

Later, sitting down, we began by asking Dr Ismail about the unmistakable feeling one gets when stepping into the old Egyptian Museum, an atmosphere distinctly different from the new one. He smiled, describing it as “iconic and the one you picture when you think of the word museum”. Built in 1902, it was the first museum ever constructed in Egypt and is more than 130 years old today. Unlike many of Egypt’s museums, which occupy former palaces or fortresses, this building “was always built to be a museum, not converted into one”. In its early decades, every artefact discovered across the country was first brought here to be stored, studied, and catalogued, allowing the museum to serve as the central hub from which treasures were later distributed to new institutions as they opened. When asked about the scale of its collection, he explained, “It has over 100,000 artefacts”, noting that while many remain in storage, “you see an extensive amount here”.

From Old to Gold

When the Grand Egyptian Museum opened, it naturally captured global attention, so we asked Dr Ismail what steps were being taken to keep the old museum relevant and vibrant. He explained that the plan had been drafted long before the new museum’s inauguration. “Of course there is”, he said. “There were plans drafted when the big museum was initially about to open. This museum will never close as its relevancy is still very important and stores a lot of artifacts”. Central to this vision is a renewed focus on Psusennes I, whose gold funerary mask he described with pride: “People like to speak about King Tut’s Mask, but this one is equally as impressive and will be a centrepiece of the museum, that and the history of gold in ancient Egypt”. He confirmed that the institution will soon be known as “The Gold Museum”, a name chosen because “it’ll have an amazing amount of gold artefacts”. Alongside its golden masterpieces, the museum will also highlight Ancient Fine Arts, “ancient paintings, statues, busts of old kings and leaders, all of this will be located here”, as well as a dedicated section for animal mummification. “There are a lot of animals from ancient times mummified, and it was a significant thing for people to do so back then” he said, explaining that even house pets such as cats and dogs were mummified and buried in Saqqara. Their recent exhibition in China featured several of these examples, and “the crowd was very intrigued”. With these three pillars, Psusennes’ treasures and pharaonic gold, ancient fine arts, and mummified animals, the old museum is poised to reinvent itself while honouring its storied past.

With more than 50,000 artefacts on display, we asked Dr Ismail how long it would realistically take for someone to see everything inside the old museum. He laughed gently, explaining, “Yeah, nobody can visit the museum and see it all in a day; it would take 4 or 5 days to truly see every single artifact on display”. He outlined the building's structure with the precision of someone who knows every corner by heart: the first level features objects spanning the earliest chapters of ancient history through the Roman period. In contrast, “the second level contains the gold and the mummified animals”. Together, the two floors create a journey so extensive and rich in history that a single visit can only scratch the surface. While walking around, we noticed some sections where a picture is displayed instead of the actual artefact, with a note stating that it is currently on display abroad at another museum. Do actions like these promote tourism to Egypt, or do people just want to see the artifact elsewhere and leave it at that? Well, we did an expo in Shanghai that attracted 2.7 million visitors”, Dr Ismail explained. “Our statistics showed that following the expo, there was a noticeable increase in Chinese tourists visiting Egypt. These exhibitions have a significant impact on our tourism; they spark interest not only in our museums but also in iconic sites such as the Pyramids, Luxor, and Aswan. It awakens their inner Egyptologist and adventurous side.”

Pyramids, Lost Artefacts and Egyptology

A topic that continues to spark curiosity online is the age-old question: How were the pyramids built, and have we finally unravelled the mystery? According to Dr Mohamed Ismail, “The conclusion is that any pyramid’s base starts as a square, proper structures are in place under the ground, then it gets built on levels”, he explained, noting that before construction begins, “the tomb is first built, storage, etc”. This underscores that planning started long before the visible pyramid was built. When asked about transporting the massive stones, Dr Ismail elaborated, “They would get the stones from Tora, they would dig them and shape them there first, then transport them across the Nile. Tora is close to Saqqara, they would wait till the Nile flooding period to transport, as it would make transportation much easier”. He further described how the blocks were raised above previous levels, “They would use a ramp made of mud and sand and spray water to make it slick, they used wooden pillars to place them properly, and we have descriptions of such”. This careful planning, ingenious engineering, and clever use of natural conditions allowed the ancient Egyptians to create one of humanity’s most enduring and awe-inspiring architectural achievements.

The question of Egyptian artifacts abroad touches on national pride, heritage, and the enduring effort to reclaim the country’s lost treasures. When asked about Egyptian artifacts that are no longer in the country, Dr Mohamed Ismail was unequivocal. “Every artifact that was taken from Egypt was done unlawfully, and must be returned”, he stated firmly. “It’s important for Egyptians to be able to see their heritage”, he added, emphasizing the cultural and national significance of these objects. In the past, it had been argued that Egypt lacked the facilities to properly house such treasures, but Dr Ismail dismissed this claim. He explained that Egypt now has the largest and most state-of-the-art facility to house artifacts, with the highest security in the world, so that argument is no longer valid. He also clarified that not all artifacts abroad are unlawful, noting that Egypt has agreements with museums, such as the one in Turin, Italy, that allow for a 50/50 trade of artefacts discovered with their assistance. The museum in Turin, officially called the Egyptian Museum, reflecting a long-standing collaboration that benefits both countries while respecting ownership rights.

Even today, Egypt continues to reveal its ancient secrets, often hiding treasures just beneath the foundations of modern life. When asked how much more could still be discovered, Dr Mohamed Ismail reflected on Egypt’s unique historical landscape. “One thing always holds, Egyptians live next to the Nile, the desert was always considered the red lane to the Egyptian or the dangerous land because danger would always come from there”, he explained. This geographical reality shaped settlement patterns over millennia, and as Egypt developed, people often built on top of existing structures. “That’s why when Egypt develops, people build on top of what other people have built, that’s why when someone digs into his home, he’ll find artefacts, on top of another house or temple that existed in the past”, he added. The result is a country where history lies literally beneath modern life, with artefacts waiting to be rediscovered even in the most unexpected places.

Passion Into Career

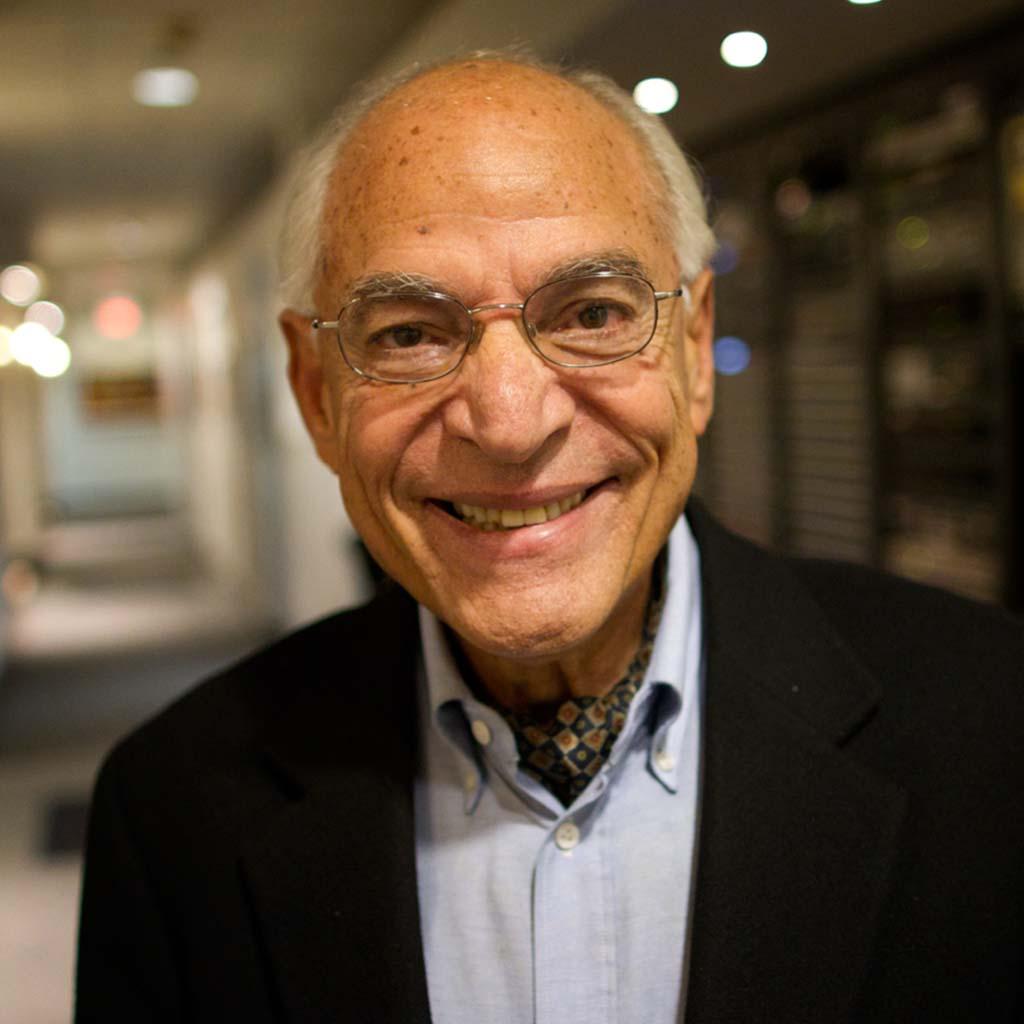

Dr Mohamed Ismail’s journey to becoming one of Egypt’s leading antiquities experts began with an international education that shaped his perspective on Egyptology. When asked why he pursued his doctorate in Egyptology in Prague, Dr Mohamed Ismail explained that the field is global. “Egyptology is an international study; the people who began it were in the West”, he said. The discipline quickly spread across France, England, Germany, and the United States, and while Egypt also developed programs, “a lot of the strong schools for the subject were in the West”. He highlighted the influence of Cherni, a renowned Egyptologist who began his studies in England and later established the subject in Prague. Dr Ismail completed his own PhD under Uslav Berner, a specialist in pyramids, gaining expertise that would inform his work preserving and interpreting Egypt’s ancient heritage.

Even for a seasoned Egyptologist like Dr. Mohamed Ismail, some discoveries stand out as both thrilling and perilous, moments that define a career spent uncovering the secrets of ancient Egypt. When asked about a standout moment in his career, Dr Mohamed Ismail recounted a daring excavation at a pyramid in Abu Seed. “We were digging into a pyramid in Abu Seed; it was the first time anyone had dug into it, although it was first found in the 1860s. The dig site was fresh, around 2019”, he explained. The pyramid’s broken and unstable condition had deterred previous explorers, leaving its secrets untouched. “We were trying to figure out how many tombs were inside, what the pyramid was about. We found a huge hidden spot inside a massive storage area and uncovered damage caused around the time of the last kingship. We found an oil lamp inside, and the damage was caused by people trying to rob the tomb. It seems the robbers saw just massive white walls and assumed if they broke them, maybe there would be something behind.” He described how the pyramid’s retaining walls and structural instability made the excavation especially perilous: “Pyramids are built using retaining walls, and due to the recklessness of their breakage, the pyramid collapsed on itself.” Reflecting on the experience, he called it “probably a defining moment of my career because it was such a huge discovery and was also dangerous due to the instability of the structure and rocks falling”.

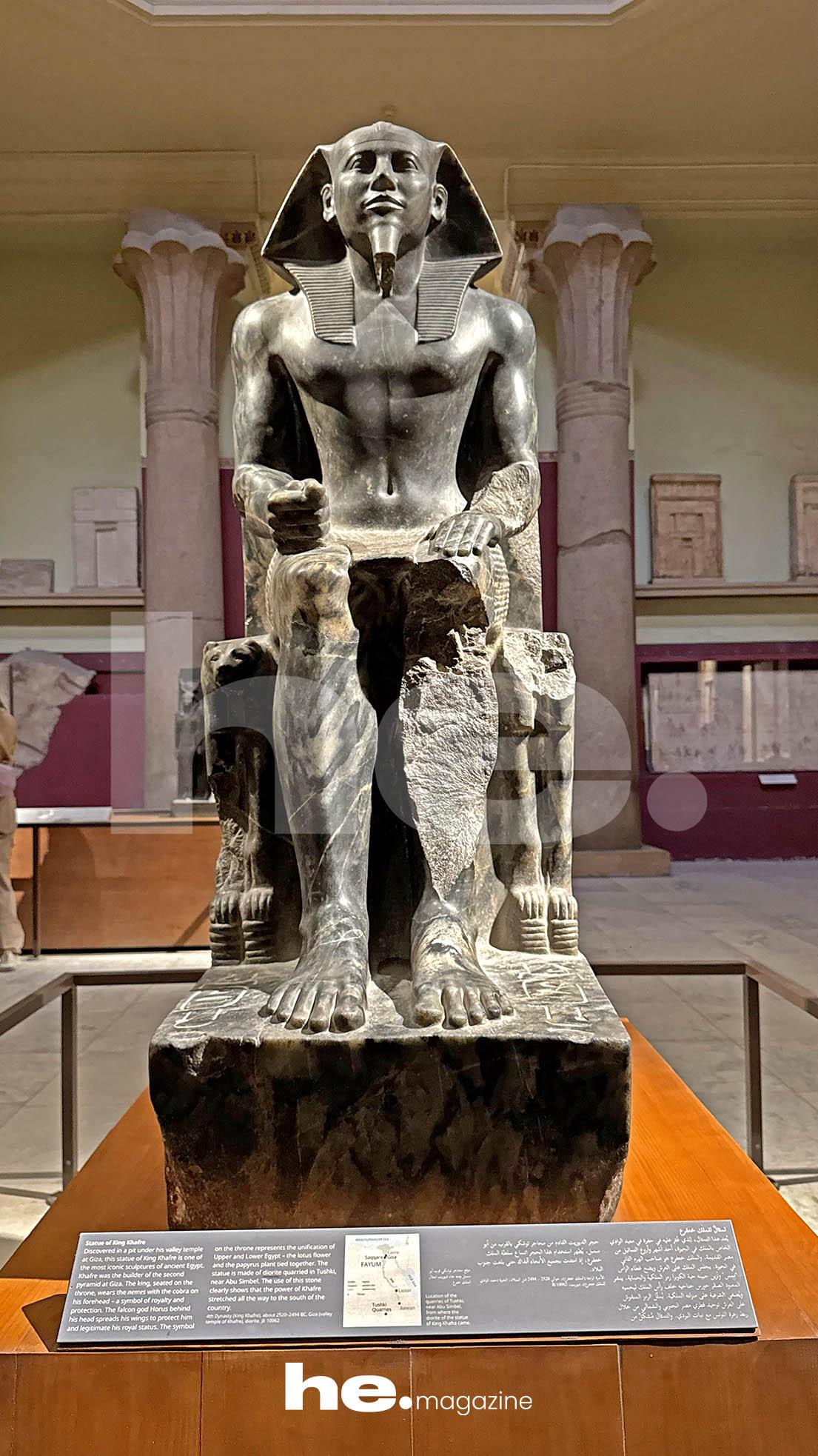

For Dr Mohamed Ismail, every artifact in Egypt’s collection tells a story that connects the past to the present, but some hold a special place in his heart. When asked what artifact holds the most personal significance to him as Head of Egyptian Antiquities, he admitted there were countless. “There’s too much to list, but for example, the Doriti Statue for King Khafra,” he began. “The statue shows the figure of the King in his splendour; the same image can be found on the 10 pound bill. The Horus that protects the king and hugs him is highly symbolic. It shows they were loved and capable of ruling. Our history is rich and beautiful, and Egypt will remain strong and beautiful”. For him, the statue embodies not only the artistic mastery of ancient Egypt but also the enduring spirit and pride of a civilization that continues to inspire.

Interview by: Amr Selim

Creative Director: Noureldin Selim

DOP: Amir Dakrory

Advertising Photographer: Hossam Horus

Photography Assistant: Moataz ElShamy

Mobile Coverage: Eslam Said

Writer: Mahmoud El Demerdash