Written by: Mahmoud Demerdash

Date: 2025-12-25

A walk with Dr. Tarek El-Gindy across the very essence of Egypt

When people think of Egyptian antiquity, they often imagine artifacts or monumental relics left by the ancestors of today’s Egyptians. But Egypt’s cities, being so ancient, are themselves living museums, littered with historical sites from countless eras.

Take Cairo, for example. Founded as the city of Fustat in 621 AD, it has been developed and reshaped by each major historical period. Layer upon layer, each generation that called it home added to the city’s character, making it a capital and epicentre for whatever was important at the time. Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, Golden Age, Enlightenment, and Modern Era influences all blend together, often unnoticed by the average passerby. This is the Cairo Dr. Tarek El-Gindy, a prominent Egyptian construction engineer and businessman with a diverse portfolio of endeavours, walks through.

One of his favourite pastimes is wandering through Cairo. On the surface, these walks lead him to hidden historical corners, places unnoticed by the casual passerby, known only to locals or dedicated historians. But beneath that, his walks serve a deeper purpose; a cathartic journey into the very fabric of the Egyptian experience. The people, the sounds, the sights, the smells, the stories, every interaction, every echo of the past and pulse of the present reveal another layer of what Egypt truly is.

He walked so often, and with such quiet passion, that many of his friends, Egyptian and foreign alike, soon found themselves following in his footsteps. Thus, was born “Walk with Tarek”, a group chat created by fellow walkers, to organize and ritualize this weekly event to satiate the appetite of the curious of mind.

We at He Magazine were invited to join one of these walks to experience the event firsthand and deepen our appreciation for the city we call home.

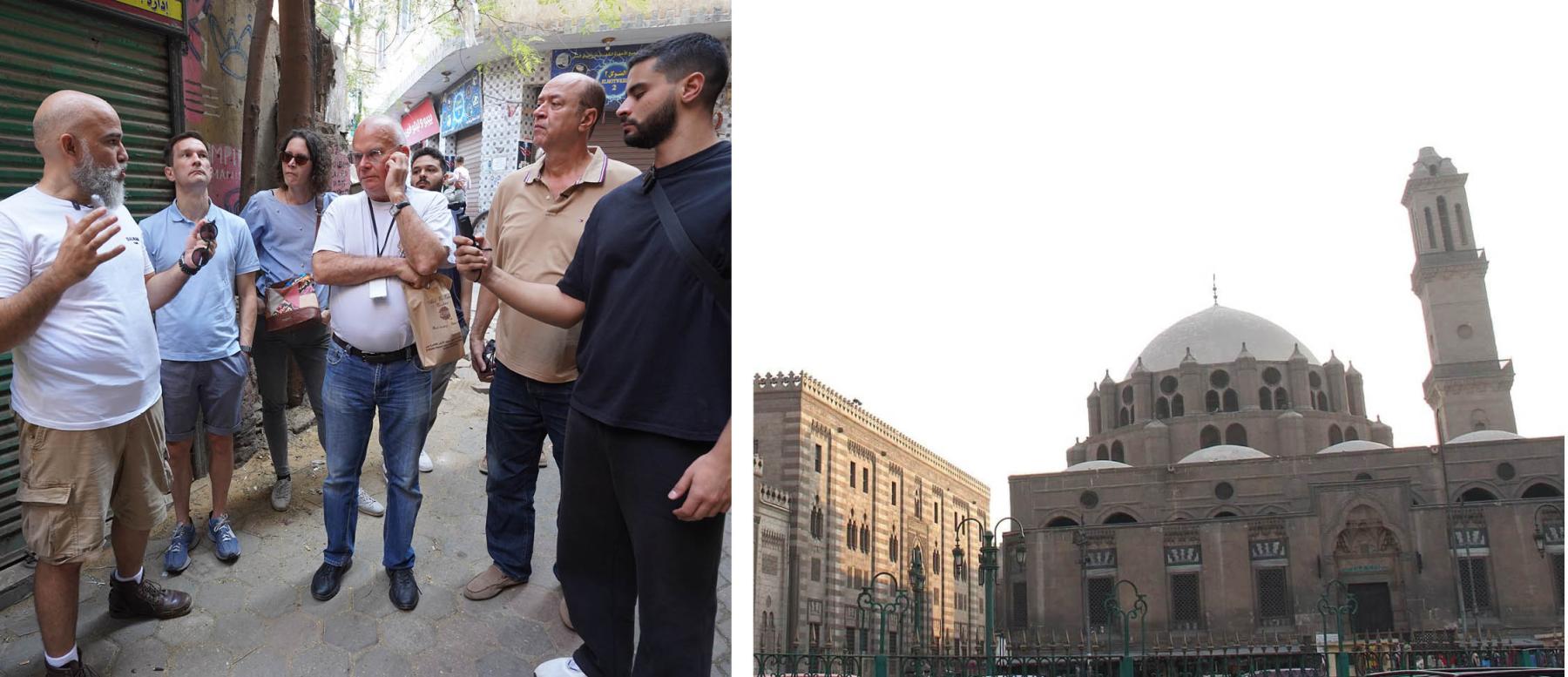

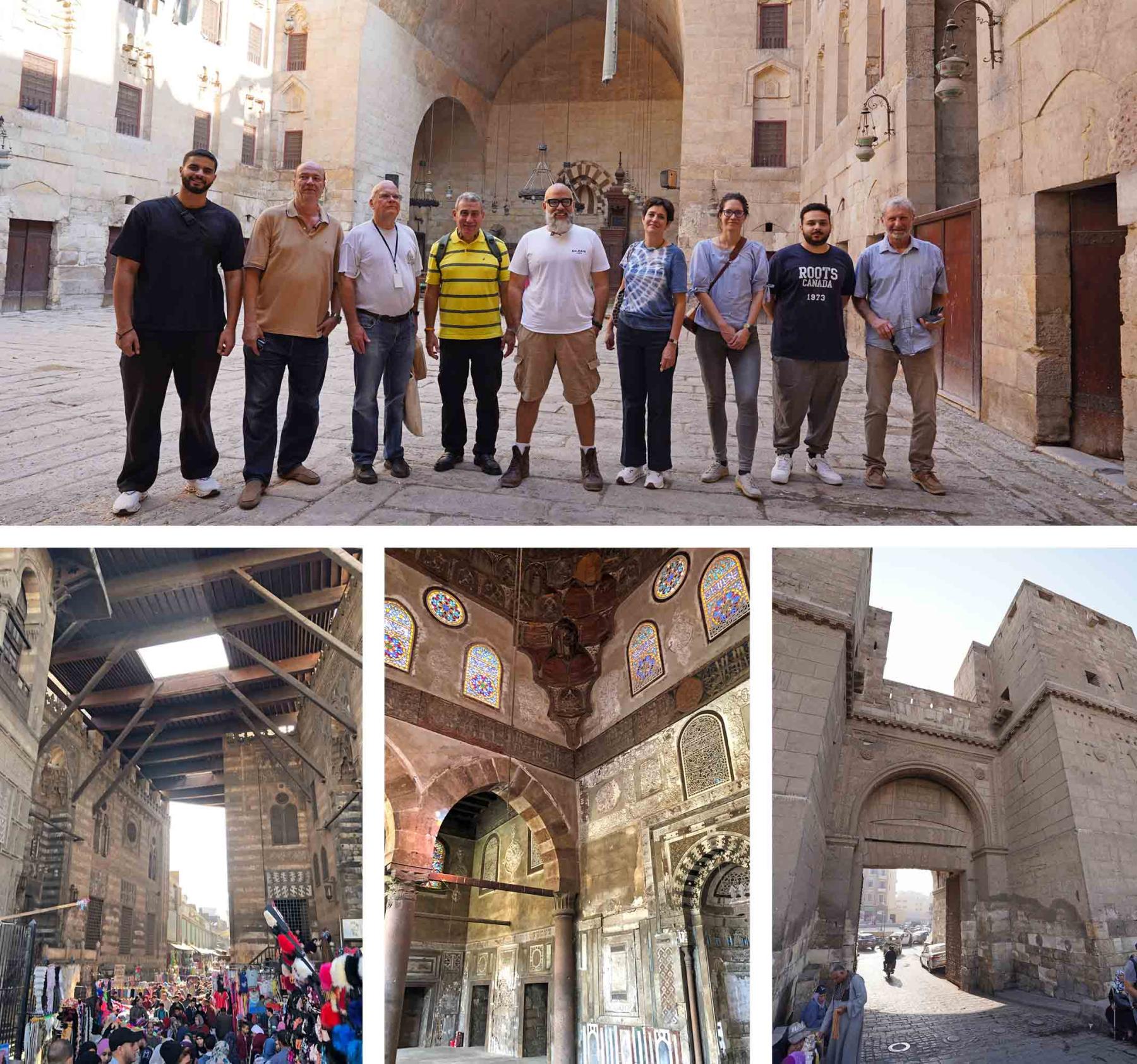

The event began promptly at 10:45 AM with a text message, gathering participants at the civilian tunnel in front of Al-Azhar Mosque. The group assembled in the heavy, historic air of Old Cairo, a mix of Egyptians and foreigners, many from Europe.

Regular attendees know how punctual Tarek El-Gindy is; he leads the walks with precise timing, rarely accommodating latecomers. Today, however, we were lucky: Dr. Tarek allowed a prominent Egyptian participant a few extra minutes, as he was arriving with tamaia sandwiches to fuel the walkers before the upcoming cardio session. The sandwiches were absolutely delicious, providing a much-needed boost of energy for the long walk and the historic exploration that lay ahead.

Our first stop was right beside us: the Mosque of Abu al-Dhahab. Completed in 1774 CE, it was commissioned by Muhammad Bey Abu al-Dhahab, an Egyptian Bey and Mamluk of ‘Ali Bey al-Kabir, served as the main ruler of Ottoman Egypt between 1772 and 1775.

The mosque was part of a larger religious and charitable complex that included a madrasa, library, takiya (Sufi lodge), sabil (water dispensary), hod (water trough), and latrines, making it one of the last major architectural complexes of its kind built by the Mamluk Beys of Egypt.

Dr. Tarek shared the fascinating story of Muhammad Abu al-Dhahab’s political manoeuvring: he betrayed his superior, Ali Bey, by siding with the Ottomans when Ali Bey attempted to assert independence and later killed him when Ali Bey tried to regain control. Dr. Tarek also pointed out interestingly, the prince built this mosque to assert the crown’s authority over the clergy, incorporating a balcony that reaches up to the location where the khutba (sermon) is delivered, a bold architectural statement of power.

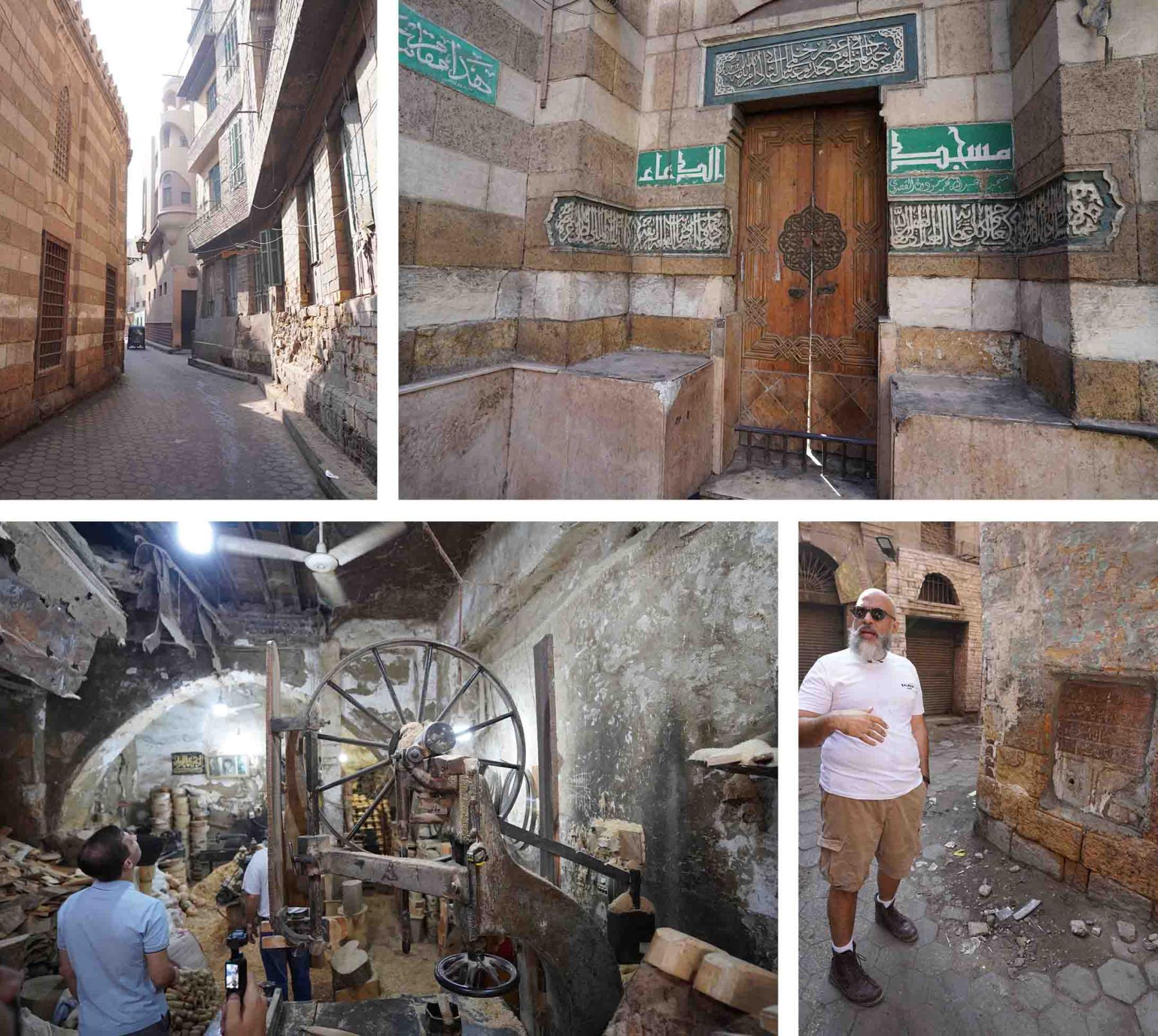

We continued down El Butneya, a very historic neighbourhood in the area, passing the bustling bazaar, before taking a left onto Mohammed Abdu Road into the older, more residential area. Along the way, we passed the Qaytbay Caravansary and stopped at a small but fascinating print shop: Abdelzaher’s Atelier.

The significance of this place lies in its preservation of centuries-old craftsmanship. Here, notebooks are still printed using traditional methods, with each page pressed and bound by hand exactly as it was hundreds of years ago. The atelier also sells ink and vintage writing utensils, and even offers customization of notebook covers, allowing visitors to create a unique, personalized piece of Cairo’s artisanal history.

Tomb’s of Prophet Benjamin & Muhammed ibn Abi Bakr

We continued deeper into the neighbourhood, taking a right into a quieter, more residential area. Dr. Tarek guided us through the narrow streets, pointing out hidden historical gems along the way. Our first remarkable stop was the tomb of Prophet Benjamin, the son of Prophet Jacob and brother of Prophet Yusuf, tucked inconspicuously among the surrounding buildings. Dr. Tarek explained that while several disputed sites claim to be his resting place, this one remains a significant and untouched historical location.

A little further down, Dr. Tarek led us to the tomb of Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, the son of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq. He shared the tragic history of Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, who was an Arab Muslim commander and governor of Egypt, killed in 658 CE (38 AH) during the First Fitna. Dr. Tarek detailed the brutal events: when forces sent by Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, led by Amr ibn al-As, seized Egypt, Muhammad was defeated, captured, and, according to early Islamic historians such as al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir, killed in a manner meant to humiliate him, with his body placed inside a dead donkey and burned.

Tarboosh Store and the Historic Wood Workshop

Dr. Tarek guided us further and pointed out a small store we were passing by, dedicated to producing traditional tarboosh hats using historic methods and antique machines. He also showed us the significance of the shop's display of original posters from the 1920s, commemorating the Egyptian revolution against the British and featuring the face of Saad Zaghloul, who would later become Prime Minister of Egypt in 1924.

Turning right, we came across Egypt’s oldest wood-cutting and processing facility, in operation since medieval times. Outside, massive logs were stacked like monuments to the craft. The patron invited us to explore freely, and walking inside felt like stepping into history. The old wooden roof looked fragile, and the sawdust-covered floor felt like walking on clouds. In the adjacent room, artisans were hard at work crafting wooden products ranging from bowls to chairs, demonstrating centuries of skill passed down through generations.

While walking through with Dr. Tarek, we came across the first Hanafya in Egypt, a historic water facility built to help people perform wudu. At the time, the king wanted to introduce this practical innovation for public use, but it faced opposition from some of the clergy, who argued that the Prophet had only performed wudu using natural running water. However, one school of thought supported the king’s idea, embracing the use of such facilities. This school eventually became known as the Hanafite school of Islamic law, shaping centuries of religious practice in Egypt.

Proceeding further, Dr. Tarek led us past an old refuelling station built by Qaid-Bey, explaining how merchants historically used it to rest and feed their camels and horses while conducting trade or staying in nearby inns.

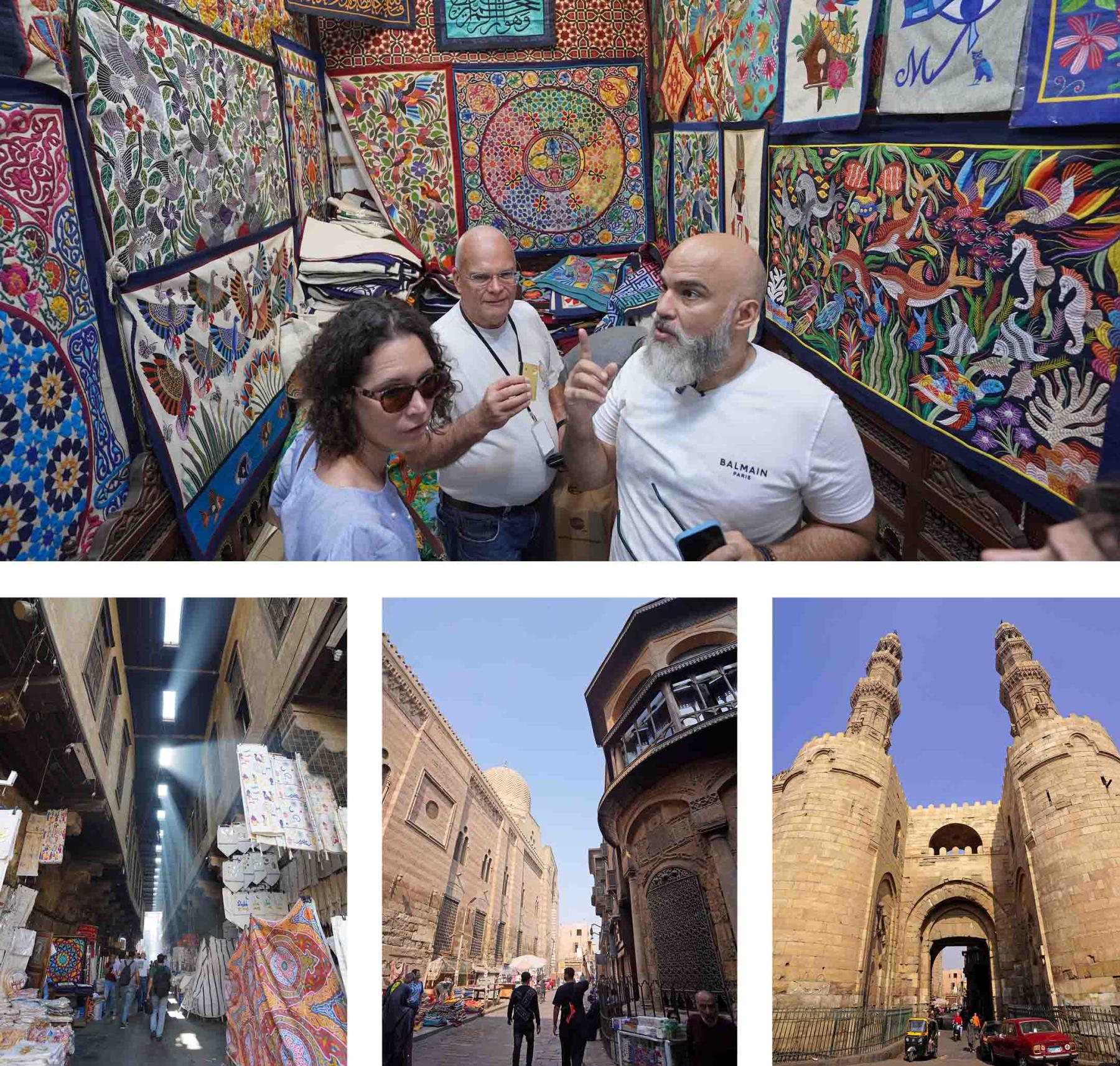

Soon, we entered Khan al-Khayamiya, the famed street of Egyptian appliqué textile art, known for its vibrant decorative fabrics that trace their origins back to Ancient Egypt. Dr. Tarek pointed out the different designs, from intricate geometric patterns to floral motifs and traditional arabesques, each reflecting centuries of craftsmanship.

Walking through the Khan, it was impossible not to be captivated; the vivid colours, delicate stitching, and variety of wares created a visual feast. Dr. Tarek encouraged us to observe how artisans carefully balanced tradition with creativity, turning a simple textile into a living piece of Egyptian heritage.

We continued our walk and arrived at Bab Zuweila, one of the three remaining medieval gates of historic Fatimid Cairo and among the city’s most iconic architectural landmarks. Dr. Tarek guided us around the gate, explaining its rich history and significance.

Named after the Zuweila tribe, whose members served as elite soldiers in the Fatimid army, Bab Zuweila is a fortified southern gate built in the 11th century (circa 1092 CE) during the Fatimid Caliphate. It served as a major entrance to the southern part of the walled city and remains the best preserved of Cairo’s historic gates.

The gate features two distinctive twin minaret towers, which visitors can climb to enjoy panoramic views of Old Cairo. Dr. Tarek shared that historically, Bab Zuweila was a site for public ceremonies, executions, and military displays, and it also marked the route for caravans departing to Mecca for Hajj, linking the city to the broader Islamic world.

Entering the Gates: Al-Mu‘izz Street and Surrounding Landmarks

As we passed through Bab Zuweila onto Al-Mu‘izz Street, Dr. Tarek led us along the historic thoroughfare, pointing out landmarks that often go unnoticed. On our right stood Sabil Nafisa al-Bayda, a historic public water fountain built by Nafisa al-Bayda, an influential and wealthy woman in 18th-century Ottoman Egypt. She was the wife of Ali Bey al-Kabir, the powerful Mamluk ruler who sought Egyptian independence from the Ottomans. Dr. Tarek explained that the sabil is located where she once sold sugar and other goods in the market and is admired for its Ottoman-Mamluk fusion architecture, featuring decorative marble, carved wood, and intricate mashrabiyya screens. He also shared how Nafisa corresponded with Napoleon and was later placed under house arrest to limit her influence after a regime change.

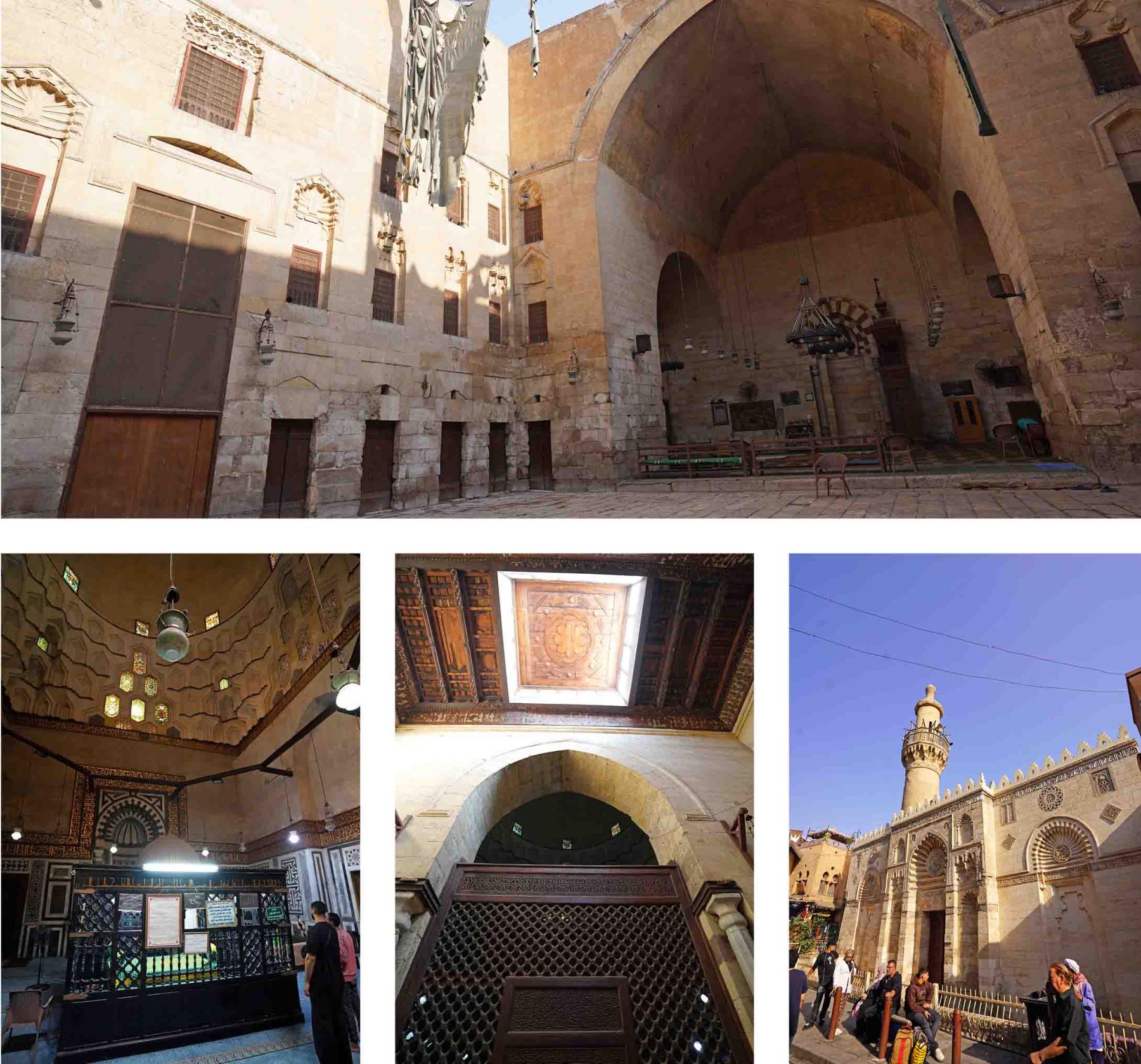

On our left stood the Sultan Al-Mu’ayyad Sheikh Mosque, a major Mamluk-era mosque built in the early 15th century, showcasing the grandeur of Cairo’s Islamic architectural heritage.

Continuing along Al-Mu‘izz Street, Dr. Tarek guided us past numerous historic buildings, including the Shrine of Sidi Muhammad al-Baghdadi, a small but significant Sufi shrine. Dr. Tarek explained that al-Baghdadi was a respected Sufi sheikh whose title reflects a lineage or connection to Baghdad, a common practice among travelling scholars and mystics.

Our next stop was the Al-Aqmar Mosque (Jāmiʿ al-Aqmar), a Fatimid masterpiece built in 1125 CE from the tombs of ancient times by Al-Ma’mun al-Bata’ihi, vizier of Caliph al-Āmir bi-Aḥkām Allāh. Dr. Tarek highlighted its unique façade, the first in Cairo to be aligned with the street while keeping the prayer hall oriented toward the qibla. The façade is decorated with interlaced Kufic inscriptions, rosettes, geometric patterns, and symbolic medallions representing the Fatimid Imams, including a famous round medallion above the door featuring the names Muhammad and Ali, emphasizing Shi’a Fatimid ideology. As we entered the courtyard, pigeons circled gracefully in a counter-clockwise motion, muting the sounds of the bustling street outside and creating a serene spot to pause and reflect, a moment of inner peace amidst the city’s historic vibrancy.

The Synagogue of Moses Maimonides

Continuing our walk, Dr. Tarek led us into Cairo’s historic Jewish Quarter, an area where the gold trade still thrives, and mobile connections are often unreliable. Here, we came across the Synagogue of Moses Maimonides, currently undergoing renovations, so tourists were unable to enter.

Dr. Tarek explained that the synagogue is a historic Jewish site in Fustat, closely associated with Moses Maimonides (1135–1204 CE), the renowned medieval Jewish philosopher, legal scholar (halakhist), and physician who served under Saladin. Inside, it reportedly houses one of the oldest Torah scrolls ever found, and beneath the synagogue are said to be the living quarters where Maimonides resided during his time in Cairo.

After passing the synagogue, Dr. Tarek guided us toward the old workshop where the Kaaba’s cover was made until the mid-1900s, pointing out how this area preserves centuries of artisanal tradition.

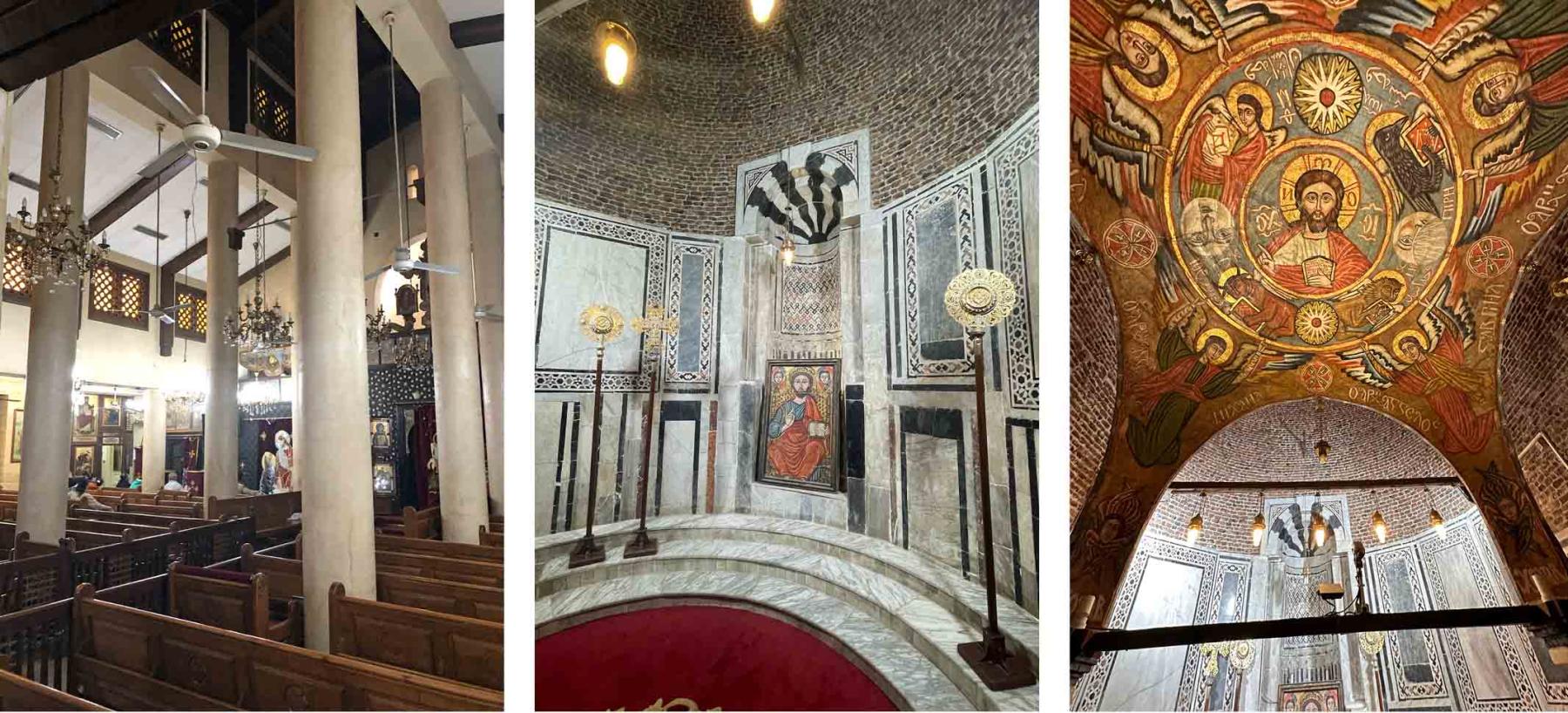

Continuing our walk, taking a right, Dr. Tarek led us to the Church of Haret Zuweila, also known as the Church of the Virgin Mary in Haret Zuweila. One of the oldest and most historically significant churches in Coptic Cairo, it dates to the 8th–9th century. Between 1400 and 1520, this church even served as the residence of the Coptic Pope.

Upon entering, it was immediately clear that the church is still active and well-maintained yet not heavily visited by tourists. Dr. Tarek guided us downstairs, where we could hear the soothing sound of a running stream, part of the fountain and water system beneath the church, creating a serene atmosphere.

The church’s massive wooden roof, Dr. Tarek explained, was built to resemble Noah’s Ark, a striking feature of its architecture. Inside, a rich collection of icons adorned the walls, including depictions of the Virgin Mary, Archangel Michael, saints, and martyrs, some dating back several centuries. An upper floor is dedicated to St. George (Mar Girgis), adding to the church’s layered spiritual and historical significance.

Mosque of Amir Baybars al-Jashankir

Nearing the end of our walk, Dr. Tarek guided us past the Mosque of Amir Baybars al-Jashankir, a historic Mamluk-era mosque built between 1306 and 1310 during the reign of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, just before Baybars briefly seized power.

Dr. Tarek explained that Baybars al-Jashankir (d. 1310) was a powerful Mamluk amir who briefly became Sultan of Egypt. His title, al-Gashankir, meaning “the taster,” reflected his palace role of ensuring the sultan’s food was safe from poison. Although he was eventually overthrown and executed, Baybars left a legacy of impressive civic and religious institutions, including this mosque, which stands as a testament to the architectural and social ambitions of Mamluk rulers.

We concluded our journey at Bab al-Nasr (The Nasr Gate), one of Cairo’s historic city gates, built in 1087 CE during the reign of Fatimid Caliph Al-Mustansir Billah. Standing there, framed by the northern part of historic Cairo and its surrounding Fatimid monuments, we could feel the centuries of history converge around us, a defensive gateway that once welcomed traders, pilgrims, and armies alike.

As the walk came to an end, we felt invigorated, our bodies warmed by exercise and our minds enriched with stories spanning a millennium. In just three hours, we had touched the layers of Egypt’s soul, ancient, medieval, and modern, interwoven with the lives of those who shaped it. Witnessing different religions and cultures coexist in such proximity, we realized that for centuries, identity was shaped not by division, but by a shared heritage as Egyptians.

For Dr. Tarek, there is no place on Earth where walking reveals history the way it does in Egypt. Nowhere else do the streets themselves speak. It’s not just the monuments or the architecture, it’s the people, their stories, their context, and the way every corner gives you a reason to stop and listen. In Egypt, you don’t search for history. You collide with it.

One turn, an old craftsman tells you how his craft has survived for centuries. Another corner and a shopkeeper explains why the wall of his store is built from recycled stones of a forgotten structure. A passerby near Bab Zuweila casually recounts how a children's song was created by a historical figure whose building is right next to you. A man in the Jewish Quarter tells you a rumour his grandfather heard about Maimonides writing in a basement room. These micro-stories are priceless. You can’t buy them, and you can’t script them. They are the living texture of Cairo.

Then there’s the life around you, the smell of roasted sweet potatoes, the man selling gooseberries from a wooden cart, the vendors who have set up their markets beside mosques for hundreds of years, continuing practices that started in the very eras those monuments were built.

The sounds, the scents, the warmth of strangers who tell you their history as if you’re family;

this is Egypt’s magic. It is a living dialogue between the past and the present, a daily reminder that Egypt’s heritage is not locked behind museum glass. It walks beside you, speaks to you, and feeds you.

At He Magazine, we often write about identity, heritage, and the meaning of belonging, but nothing prepared us for what we felt while walking through Cairo with Dr. Tarek. We believed we understood our connection to Egypt, its history, its culture, its spirit, but that walk revealed how little we had truly grasped until we experienced it firsthand. Egypt lives. Its history breathes. And as the stories, the streets, the scents, and the centuries unfolded around us, a realization struck with overwhelming clarity: this is our inheritance, our bloodline, the soul to which we have always been anchored.

For the first time, we experienced Egypt not as an idea or a memory, but in its totality, vivid, immense, immaculate. The magnitude of the moment felt almost impossible to capture in words, too layered and too alive to be neatly contained on a page, as if the very soul of Cairo refuses to be reduced to ink.

And it wasn’t just one of us who felt this transformation; all of us at He Magazine, privileged to take that walk together, found our love for Egypt, already deep and unwavering, growing even stronger. Our appreciation didn’t simply increase; it rooted itself more deeply in our identity and reinforced why we do what we do. For us, this experience was profound; for Dr. Tarek, it was simply another Friday.

Photography & Videography: Mohamed Fathi

Written by: Mahmoud El Demerdash

Video Editor: Mohamed Ahmed